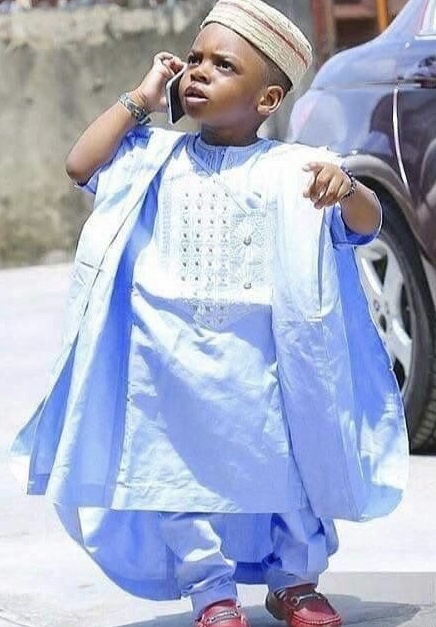

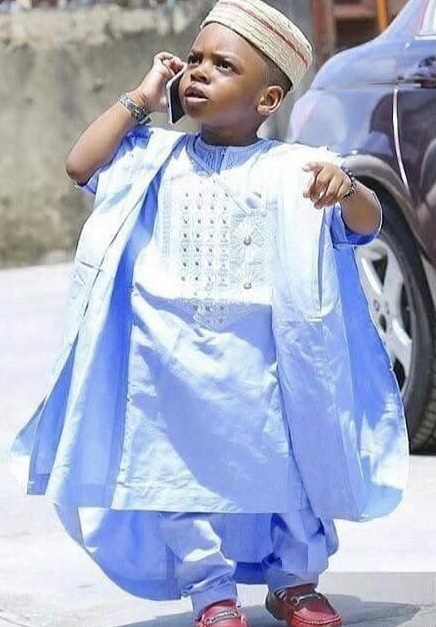

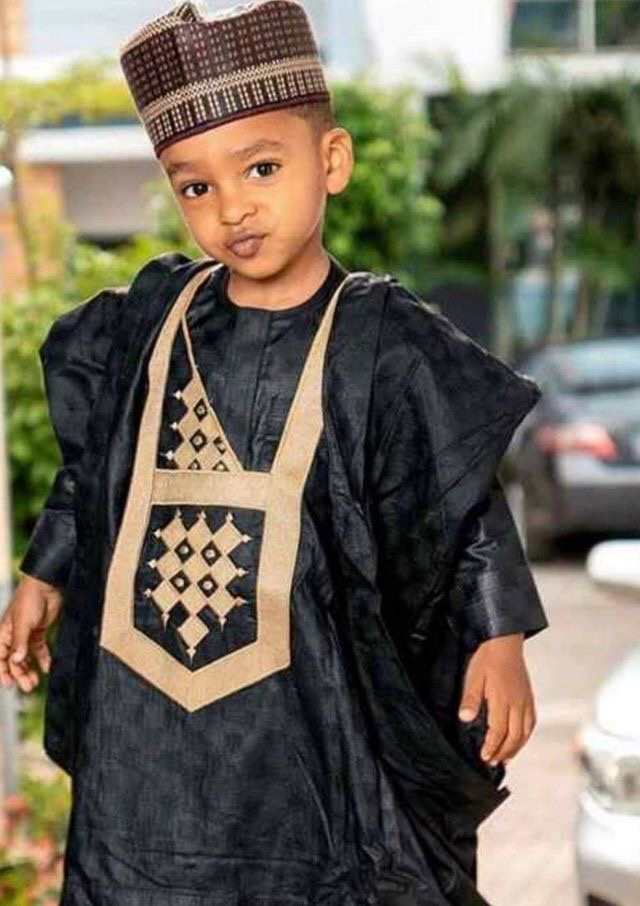

Agbada is a four-piece male attire found among the Yoruba of southwestern Nigeria and the Republic of Benin, West Africa. It consists of a large, free-flowing outer robe (awosoke), an undervest (awotele), a pair of long trousers (sokoto), and a hat (fìla).

The outer robe-from which the entire outfit derives the name agbada, meaning “voluminous attire”-is a big, loose-fitting, ankle-length garment. It has three sections: a rectangular centerpiece, flanked by wide sleeves. The centerpiece-usually covered front and back with elaborate embroidery-has a neck hole (orun) and big pocket (apo) on the left side. The density and extent of the embroidery vary considerably, depending on how much a patron can afford. There are two types of undervest: the buba, a loose, round-neck shirt with elbow-length sleeves; and dansiki, a loose, round-neck, sleeveless smock.

The Yoruba trousers, all of which have a drawstring for securing them around the waist, come in a variety of shapes and lengths. The two most popular trousers for the agbada are sooro, a close-fitting, ankle-length, and narrow-bottomed piece; and kembe, a loose, wide-bottomed one that reaches slightly below the knee, but not as far as the ankle. Different types of hats may be worn to complement the agbada; the most popular, gobi, is cylindrical in form, measuring between nine and ten inches long. When worn, it may be compressed and shaped forward, sideways, or backward. Literally meaning “the dog-eared one,” the abetiaja has a crestlike shape and derives its name from its hanging flaps that may be used to cover the ears in cold weather. Otherwise, the two flaps are turned upward in normal wear.

The labankada is a bigger version of the abetiaja, and is worn in such a way as to reveal the contrasting color of the cloth used as underlay for the flaps. Some fashionable men may add an accessory to the agbada outfit in the form of a wraparound (ibora). A shoe or sandal (bata) may be worn to complete the outfit.

It is worth mentioning that the agbada is not exclusive to the Yoruba, being found in other parts of Africa as well. It is known as mbubb (French, boubou) among the Wolof of Senegambia and as riga among the Hausa and Fulani of the West African savannah from whom the Yoruba adopted it.

The general consensus among scholars is that the attire originated in the Middle East and was introduced to Africa by the Berber and Arab merchants from the Maghreb (the Mediterranean coast) and the desert Tuaregs during the trans-Saharan trade that began in the pre-Christian era and lasted until the late nineteenth century. While the exact date of its introduction to West Africa is uncertain, reports by visiting Arab geographers indicate that the attire was very popular in the area from the eleventh century onward, most especially in the ancient kingdoms of Ghana, Mali, Songhay, Bornu, and Kanem, as well as in the Hausa states of northern Nigeria. When worn with a turban, the riga or mbubb identified an individual as an Arab, Berber, desert Tuareg, or a Muslim. Because of its costly fabrics and elaborate embroidery, the attire was once symbolic of wealth and high status. Those ornamented with Arab calligraphy were believed to attract good fortune (baraka). Hence, by the early nineteenth century, the attire had been adopted by many non-Muslims in sub-Saharan Africa, most especially kings, chiefs, and elites, who not only modified it to reflect local dress aesthetics, but also replaced the turban with indigenous headgears. The bigger the robe and the more elaborate its embroidery, the higher the prestige and authority associated with it.

There are two major types of agbada among the Yoruba, namely the casual (agbada iwole) and ceremonial (agbada amurode). Commonly called Sulia or Sapara, the casual agbada is smaller, less voluminous, and often made of light, plain cotton. The Sapara came into being in the 1920s and is named after a Yoruba medical practitioner, Dr. Oguntola Sapara, who felt uncomfortable in the traditional agbada. He therefore asked his tailor not only to reduce the volume and length of his agbada, but also to make it from imported, lightweight cotton.

The ceremonial agbada, on the other hand, is bigger, more ornate, and frequently fashioned from expensive and heavier materials. The largest and most elaborately embroidered is called agbada nla or girike. The most valued fabric for the ceremonial agbada is the traditionally woven cloth popularly called aso ofi (narrow-band weave) or aso oke (northern weave). The term aso oke reflects the fact that the Oyo Yoruba of the grassland to the north introduced this type of fabric to the southern Yoruba. It also hints at the close cultural interaction between the Oyo and their northern neighbors, the Nupe, Hausa, and Fulani from whom the former adopted certain dresses and musical instruments. A typical narrow-band weave is produced on a horizontal loom in a strip between four and six inches wide and several yards long. The strip is later cut into the required lengths and sewn together into broad sheets before being cut again into dress shapes and then tailored.

A fabric is called alari when woven from wild silk fiber dyed deep red; sanyan when woven from brown or beige silk; and etu when woven from indigo-dyed cotton. In any case, a quality fabric with elaborate embroidery is expected to enhance social visibility, conveying the wearer’s taste, status, and rank, among other things. Yet to the Yoruba, it is not enough to wear an expensive agbada- the body must display it to full advantage. For instance, an oversize agbada may jokingly be likened to a sail (aso igbokun), implying that the wearer runs the risk of being blown off-course in a windstorm. An undersize agbada, on the other hand, may be compared to the body-tight plumage of a gray heron (ako) whose long legs make the feathers seem too small for the bird’s height. Tall and well-built men are said to look more attractive in a well-tailored agbada. Yoruba women admiringly tease such men with nicknames such as agunlejika (the square-shouldered one) and agunt’asoolo (tall enough to display a robe to full advantage).

That the Yoruba place as much of a premium on the quality of material as on how well a dress fits resonates in the popular saying, Gele o dun, bii ka mo o we, ka mo o we, ko da bi ko yeni (It is not enough to put on a head-gear, it is appreciated only when it fits well).

Bibliography

De Negri, Eve. Nigerian Body Adornment. Lagos, Nigeria: Nigeria Magazine Special Publication, 1976.

Drewal, Henry J., and John Mason. Beads, Body and Soul: Art and Light in the Yoruba Universe. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1998.

Eicher, Joanne Bubolz. Nigerian Handcrafted Textiles. Ile-Ife, Nigeria: University of Ife Press, 1976.

Heathcote, David. Art of the Hausa. London: World of Islam Festival Publishing, 1976.

Johnson, Samuel. The History of the Yorubas. Lagos, Nigeria: CMS Bookshops, 1921.

Krieger, Colleen. “Robes of the Sokoto Caliphate.” African Arts 21, no. 3 (May 1988): 52-57; 78-79; 85-86.

Lawal, Babatunde. “Some Aspects of Yoruba Aesthetics.” British Journal of Aesthetics 14, no. 3 (1974): 239-249.

Perani, Judith. “Nupe Costume Crafts.” African Arts 12, no. 3 (1979): 53-57.

Prussin, Labelle. Hatumere: Islamic Design in West Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Fashion History, Love to Know Clothing Types and Styles.

@wizzy, Antropologist & African Studies researcher.