The one-drop rule is tired.

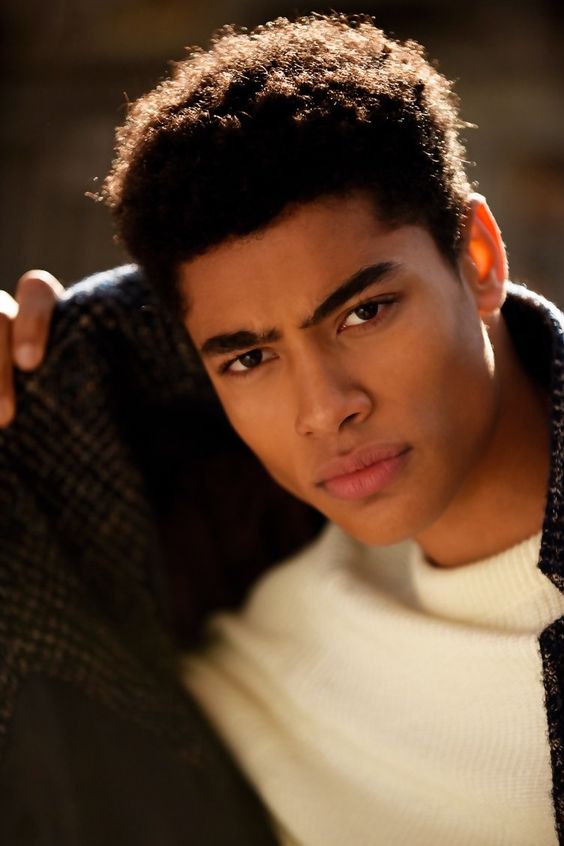

Before you roll your eyes at the title of this article, please know that I recognize that light-skinned Black people are and will always be Black. That said, we must honestly acknowledge the vast difference between merely having light Black skin and being white-passing.

Although light skinned Black people benefit from colorism – a systemic privileging of those with more phenotypical proximity to whiteness – they still face the burden of Blackness in a white supremacist world. Their Black features in combination with darker-than-white melanated skin means that racism is still a thing that works against them.

Those who can pass as white or racially ambiguous (as light skinned Black women cannot) are bestowed undeniable privileges that we must address as a society.

At the 2018 BeautyCon Festival, biracial actress Zendaya Coleman famously admitted: “I’m Hollywood’s acceptable version of a Black girl”. She continued, “Can I honestly say that I’ve had to face the same racism and struggles as a woman with darker skin? No, I cannot.”

I’m a fan of Coleman’s work (Euphoria is a must-watch!) and I think her quote reveals the hugely preferential treatment that biracials receive compared to unambiguous Black women. The ability to look at somebody and question their ethnicity and race is a privilege that unambiguous Black people do not have – regardless of skin tone variations.

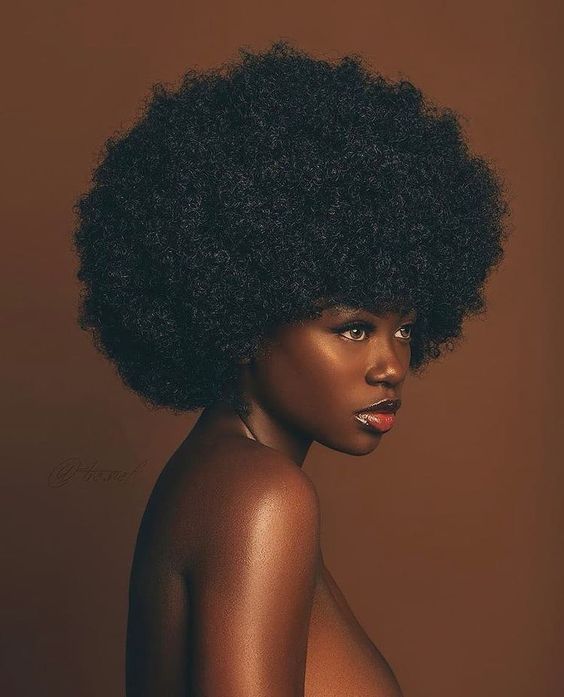

While many biracial people can and do choose to identify with their Black sides, unambiguous Black people cannot choose the wearing of their Blackness. We are Black in the morning, at the post office, and in traffic. Blackness is not a tool to carry and wear according to one’s desire.

Instead, identifying biracial people as Black only harms unambiguous or monoracial Black people while placing biracials on an undeniable pedestal. We live in a world where whiteness and proximity to whiteness is everything – those with more phenotypical “whiteness” are given privileges and benefits over others who stand farther from this ideal.

In the 1917 American Journal of Sociology, E.B. Reuter claimed that what made “exceptional Negros” so extraordinary was the fact they were “men of more Caucasian than Negro blood”. Reuter suggests that mulattoes or mixed/biracial people were exceptional precisely because of their white genes.

Unfortunately, this sentiment still lingers heavily in the Black community. As a result, lumping Blacks and biracials together inevitably acts in the favor of biracials, at the expense of Black people, due to the structural immensity of whiteness, white supremacy and white privilege.

This fact is evident in all spheres of life, but it’s particularly noticeable in Hollywood. As Jalen Rose acknowledged in Nubian Message, “Black people of a lighter shade rarely find trouble being casted in major roles in films and TV shows. However, dark-skinned actors, especially women, have much more difficulty when it comes to being cast in similar roles.”

It is unclear whether Rose includes biracials in his statement about Black people of a lighter shade, but nonetheless, his observation further proves the point about biracial privilege over unambiguous Blacks.

As you travel down the spectrum away from whiteness and its ideals, the benefits subside and decrease. Therefore, allowing Biracial people to identify solely as Black and take up spaces that belong to unambiguous Blacks harms those who cannot choose their Blackness.

Black women, in particular, face the brunt of this form of racial categorization.

As Tamara Winfrey Harris writes in The New York Times:

“Black women — real ones — live at the nexus of that oppression and enduring sexism. The gender pay gap is steeper for them. They are more likely than their white counterparts to live in poverty, to be victims of domestic homicide and sexual assault. If Tyisha Miller and Rekia Boyd, black women who were victims of extrajudicial violence, had been able to slide into whiteness — for just a moment — they might still be alive.”

1. Biracial People Cannot Relate To The Full Experience of Blackness In America

Harris finishes, “We cannot proclaim the black race a nebulous concept, while strictly policing whiteness and the privileges of that identity.” Just as there are standards when falling cleanly in line with whiteness, there should also be exclusive standards to help us better identify between Blacks and biracials.

While biracial people may culturally identify with the cultural experience of Blackness, few of them can truly and fully identify with the everyday experiences of Black people in today’s world of white supremacy. As a result, we would do well to draw a line of distinguishment and properly classify biracial people as what they are – biracial.

As previously mentioned, unambiguous Black people do not get to choose whether to identify as Black. We are Black everywhere and everyday.

Thus, it’s unfair to pretend to share the same experience as an ambiguous person with the ability to choose which race they “identify with”. If you can choose what your race to identify with, you’re not Black. Simple.

2. Biracial Cultural Wins Do Not Trickle Down To Unambiguous Black People

Consequently, I refuse to tout biracial representation as a win for unambiguous Black women like myself because biracial representation doesn’t consistently trickle down to dark-skinned Black women who look like me.

Instead, we see lighter skinned and biracial actresses all over the screen, while their darker counterparts are left out. In reality, classifying biracial actresses as Black locks out unambiguous, monoracial and dark-skinned Black female actresses.

If we count biracial actresses as Black, then there are technically plenty of Black actresses present in Hollywood (think Zoe Kravitz, Amandla Stenberg, Yara Shahidi, etc). However, a deeper look will reveal that few of these women look like the average monoracial Black woman.

Hollywood has an evident preference for racially ambiguous biracial women. And secondly, the presence of these women is used to silence real Black women when we ask for genuine positive promotion and representation.

For example, the 2016 biopic Nina was an opportunity to represent and pay homage to the prolific musician Nina Simone, a dark-skinned Black woman. Instead, the film’s casting director Cynthia Mort hired biracial actress Zoe Saldana to play Simone.

The film was rightfully met with vehement backlash as to why Saldana appeared with a nose prosthetic and Blackface, when it would’ve been easier to cast an actual Black woman who naturally looked like Nina Simone.

While Saldana has since apologized for her role in this tone-deaf film, the issue still speaks to a larger issue: how refusing to acknowledge the differences between biracial and Black people allows biracial people to exist in spheres that are not meant for them.

Hollywood rarely casts dark-skinned Black people to play biracial people and characters – so why cast biracial people in roles that are meant for Black people?

3. Yes, Many Black Americans Aren’t 100% Black – But That Doesn’t Mean There’s No Difference In The Average Experience of Those Who Are Phenotypically Black And Those Who Appear Racially Ambiguous

Mixed-ish, for example, is a show that represents the experiences of mixed/biracial people. The cast and narratives, however, do not reflect that of most Black Americans – the majority of which are unambiguous and phenotypically Black.

If mixed people and Black people are all the same, as many claim, then a show like Mixed-ish would see a cast of all types of Black people (mixed, light-skinned and dark-skinned). Instead, the majority of the cast appears racially ambiguous and that is because there is a clear phenotypic difference between monoracial Blacks and biracial Blacks.

4. Biracial Feelings And Experiences Are Often Placed On A Pedestal In The Black Community

I would argue that Black people have been made hyper aware of biracial issues, struggles and experiences – to the point where we respond defensively to valid points and questions about Black racial exclusivity.

University of Michigan social psychologist Arnold Ho said in a study, “Discrimination against black-white multiracials is widely acknowledged in the black community, at least according to our respondents.”

On the other hand, society rarely acknowledges how refusal to recognize the difference between biracial and Black people affects unambiguous Black people.

When discussing how classifying biracial women as Black reduces the opportunities for unambiguous Black women to have their own spheres, the conversation is met with dishonest discourse.

When colorism is mentioned with our lighter-skinned Black counterparts, the shift of the conversation moves from those who face the brunt of colorism (dark-skinned Black women) to the stories and experiences of lighter-skinned Black women or mixed women.

Just as white people often hijack conversations about race and the Black experience in America, biracial people hijack honest conversations about Black racial exclusivity with complaints about confusion in racial identity.

5. If Biracial People Aren’t Black, Then What Are They?

There’s nothing wrong with asking biracial people to recognize and navigate the nuances of culturally identifying with Blackness, while asking that they not take up spaces for unambiguous Black people.

There’s nothing wrong with recognizing both your Blackness and whiteness and choosing neither side predominantly, but walking the fine line between and within both intersecting identities. Blue and red doesn’t make red or blue; it makes a new color – purple, which contains elements of both colors, yet takes on its own unique characteristics.

All I’m asking is that we begin to keep exclusive spaces and roles for Black women, while refusing to allow biracial women to undermine us in our own spheres. Instead, creating separate categories and spaces for ambiguous people who don’t fall cleanly into whiteness, Blackness or other, is the best way to go.

Special Thanks to sorellamag.org for the text and the contents.