This is one of the few books on Yoruba religion written from a Yoruba viewpoint; it contains a considerable amount of material–songs and verses quoted with English translations, which has never before been recorded.

In all the previous works which have reference to the religion of the Yoruba, the Deity has been assigned a place which makes Him very remote, of little account in the scheme of things. Very few people who really know the Yoruba can escape the uneasy feeling that there is something inadequate, to say the least, about such a notion; and it is that “uneasy feeling” that leads understanding what the Yoruba actually know and believe about the Deity.

This book thus presents a new study of the belief of the Yoruba with the specific aim of emphasising their concept of the Deity.

In order to do this objectively, Bolaji Idowu has endeavoured throughout, as much as possible, to let the Yoruba themselves tell us what they know and believe, as they are so well able to do through their myths, in the recitations of their philosophy, with their songs and sayings, and by their liturgies.

To translate Yoruba verses and sayings into English and yet preserve their exact meaning is not an easy task. He, however, tried to meet the difficulty by being rather literal and keeping very close to the original in his translations.

Throughout this work, he has reserved the title “Deity” for the Supreme Being alone, where he is not calling Him by His Yoruba name; and for the “gods many and lords many” he has used either the generic designation of “divinity” (or “divinities” as the case may be) or call them by their Yoruba generic name, orìs + ̩à when he is not using their individual names.

One secondary aim which he sought to fulfill through this book is to supply one of our deeply felt needs in the matter of good standard textbooks on Yoruba beliefs and thoughts.

But … let’s start from the beginning.

Creations stories hold me captive. It’s a fascination that began when I first listened to how elder villagers used to tell me stories about the formation of the universe and the evolutionary history of life on Earth. I got in bliss when I gained an understanding of the correlation between the story of the Fall of Man (which is a term used in Christianity to describe the transition of the first man and woman from a state of innocent obedience to God to a state of guilty disobedience) and the complexification of consciousness that occurred as a result of the evolution of the human brain, an event that naturally caused the early human to be “expelled from a state of innocence” into one rife with self-consciousness and inner conflict. For me, the intuitive depth of creation stories inspire wonder, and so I found myself rapt as I was drawn into Olodumare: God in Yoruba Belief by E. Bolaji Idowu.

Idowu, the First Patriarch of the Methodist Church of Nigeria from 1972 to 1984, published his first book, a theogony, and cosmogony of the Yoruba religion of West Africa, in 1962. It was the result of his doctoral thesis, a heroic effort considering it was written during a violent anti-witchcraft craze led by both Christians and Muslims targeting Yoruba priests and priestesses. Idowu’s aim was to dispel the idea “circulated abroad and widely accepted… that the religion of West Africa is something without any real value – something in which barbaric crudeness is mercifully relieved by a touch of the ridiculous.” Clearly, however, the Yoruba religion was met with more than just condescension during Idowu’s time. For some it evoked a brutal fear, perhaps not just by perceived threats of differences, but also or perhaps even more so by similarities, for the Yoruba religion has many things in common with the Abrahamic religions, including but not limited to a Fall of Man and an underlying monotheistic concept of God.

The Yorubas, population approximately 45 million, occupy southwest Nigeria. They are one of the largest ethnic groups in Nigeria endowed with rich cultures, and in several ways, one of the most interesting peoples of Africa. Their tradition gives them a unique place among African societies. They have contributed to the cultures of the Caribbean and South America, in particular Cuba and Brazil, where the Yoruba religion is practiced. Within Nigeria, the Yoruba are one of the three largest ethnic groupings. According to Idowu, The Yoruba comprise several clans which are bound together by language, traditions, religious beliefs, and practices.

One certainty about the Yoruba is the fact that it is very hard to find an indigenous Yoruba who does not believe in the Supreme Being. If such a person exists, he or she must have been exposed to non- African influences. The Yoruba believe in the Supreme Being who is responsible for the creation and maintenance of the universe.

Baudin, a Roman Catholic priest of French descent, wrote about the Yoruba God in these words:

The Blacks have neither statutes, nor symbols to represent God. They consider him as the Supreme Primordial Being, author, and father of the gods and spirits. At the same time, they think that god after beginning the organization of the world, charged Obatala to finish it and govern it, then withdrew and went into an eternal rest to look after his happiness.

Idowu implies that the West does not have a clear grasp of the concept of God. The concept of God is not a monopoly of the traditional society. Upon further scrutiny of Baudin’s statement, one notes that he does not appreciate the fundamental idea of God as conceived by the Yoruba especially with regard to the creation. The most troubling thing is his racial overture and his condescending attitude toward the Yoruba.

In the 19th century, a British officer named A. B. Ellis claimed that:

Olorun is the sky god of the Yoruba, that is, he is deified firmament, or personal sky . . . He is merely a natured-god, the personally divine sky, and he only controls phenomena connected in the native mind with the roof of the world . . .Since he is too lazy or too indifferent to exercise any control over earthly affairs, man on his side does not waste time in endeavoring to propitiate him, but reserves his worship and sacrifices for more active agents . . . .In fact, each god, Olorun included, has, as it were, his own duties, . . . he cannot trespass upon the rights of others.

Here again, we see the ethnocentrism of western scholars. In the above observation, first, Ellis displays his lack of understanding about Olorun by associating Olorun with a “natured god”. Second, Ellis mixes Olorun with Eledaa. What Ellis says is far from the truth when he asserted that Eledaa and Olorun mean two different things. Olorun, in the Yoruba terminology, refers to the Supreme Being and Eledaa refers to “He who controls rain” while Olodumare is “Replenisher of brooks”. In actuality, these terms (Olorun, Olodumare, and Eledaa) are interchangeable for the same God, Olorun. Eledaa means he who creates in Yoruba language and Olodumare means the Almighty – the Supreme Being. Ellis’ error is that he ranks Olorun with the divinities when he said: “Olorun cannot trespass upon the rights of the others”.

By others, Ellis implies that Olorun is in no way superior to the divinities. This is false. The Yoruba people believe that Orisa cannot exist independent of the Supreme Being. The Yoruba view the divinities as “ministering spirits and intermediaries between man and the Supreme Being.” One can liken them to the angels of God, who are ministering to the Supreme Being according to Christian concepts. Ellis clearly demonstrates his lack of cultural competence when he claims that worship is rendered entirely to agents who are more active than Olorun. Ellis’ comments reflect further inaccuracies when he says that the Supreme Being is too lazy, distant, and indifferent.

The best, scholarly research, into the concept of the Supreme Being among the Yoruba comes from E.B. Idowu. In his book, Idowu states “Olodumare is the traditional name of the Supreme Being and that Olorun, though commonly used in popular language appears to have gained its predominating currency in consequence of Christian and Moslem impact upon the Yoruba thought”.

These scholars’ views of the concept of God has been an attempt to identify major errors in the scholarly assertions. Unfortunately, most of the scholars reviewed, demonstrated in their analyses, a lack of cultural sensitivity for those who are racially different.

To achieve an accurate view of the Yoruba concept of the Supreme Being, it is important to examine the names and the meanings, which are associated with the Supreme Being. It should be emphasized that the Yoruba interchangeably use the terms listed below to describe the supreme God. To the Yoruba, they are known as “oriki”, loosely translated as “nicknames”. According to Idowu, the Supreme Being is “acknowledged by all the divinities as the Head whom all authority belongs and all allegiance is due. He is no one among many. His status of supremacy is absolute . . . In worship, the Yoruba hold him ultimately first and last in man’s daily life. He is the preeminence. These names and their definitions follow:

- Olodumare: The concept connotes one who has the fullness or superlative greatness, the everlasting majesty upon whom man can depend.

- Olorun: The owner (Olorun), the heaven above or the Lord whose home is in heaven above. Sometimes the Yoruba use Olorun Olodumare together. This double word means the Supreme Being whose abode is in the heaven.

- Eledaa: The creator. As the name suggests, the Supreme Being is responsible for all creation.

- Alaaye: The word means the living one. This means that the Yoruba believe that God is everlasting.

- Elemi: Elemi is the keeper of life. Used to refer to the Supreme Being, it suggests that all living Beings owe their breath of life to the Supreme Being. It is believed by the Yoruba that when the keeper of life withdraws “life breath”, the living soul dies.

- Olojo Oni: This word means the owner and controller of this day or of the daily happenings. To call Him Olojo Oni portrays that all men and women totally depend of the Supreme Being.

Attributes of the Supreme Being

To further enhance understanding of Yoruba belief, it is also necessary to explore the characteristics of Olodumare that differentiates God from other things that he created.

- He is the Creator. Among the Yoruba, the myth of creation holds that in the beginning the world was a marshy, watery wasteland. Olodumare and some divinities lived in heaven, descending and ascending by means of spiders’ webs or a chain. They frequently visited the earth, particularly for hunting. Humankind was non-existent because there was no land.

One day, Olodumare summoned His Chief, Orisa-nla, to his presence and commissioned him that He (Olodumare) wanted to create firm ground. For materials, Olodumare gave him loose earth in a snail shell, a pigeon and a hen. Orisa-nla descended to the marshy wasteland. He threw the earth from the shell. He put the chicken and the hen on earth, and they started to scratch and scatter the soil about. Orisa-nla reported to Olodumare that the work had been completed. Olodumare then dispatched a chameleon to go to inspect the work. The chameleons told Olodumare that the work was done but not dry enough. The chameleon was sent the second time. This time the report was that the land was wide and dry.

Olodumare next instructed Orisa-nla, the chief divinity, to equip the earth. Orisa-nla took with him Orunmila, the oracle divinity, as his advisor and counselor. The mission was to plant trees and to give food and wealth to humans. He provided the palm tree to be planted to provide food, drink, oil and leaves for shelter.

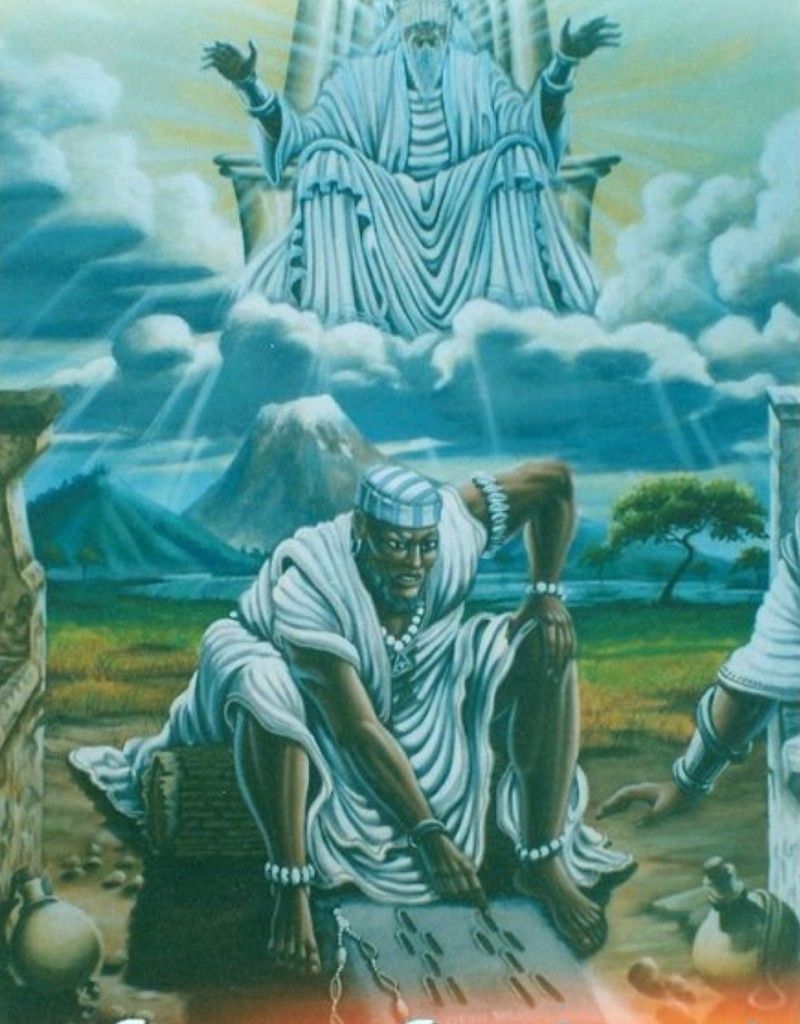

Following the equipping of the earth, Orisa-nla was asked to lead a delegation of sixteen persons already created by Olodumare. To populate the earth, Olodumare asked Orisa-nla to mold human forms. Orisa-nla molded human forms and kept them lifeless. Occasionally, Olodumare would come and breathe life into these forms. All that Orisa-nla could do was to mold the lifeless, human forms, but he lacked the power to give them life. The creation of life was entrusted to the Supreme God, Olodumare. It is said that Orisa-nla became envious of Olodumare for not sharing the ability to create life with him. So one day, when he had finished molding human forms, he hid himself in with the forms overnight so that he could watch Olodumare. But, Olodumare, being all knowing, put Orisa-nla to sleep, and when he awoke, the molded human forms had come to life. This is the story of the creation as told by the Yoruba. - He is Unique. The Yoruba believe that Olodumare is unique. This means that He is the only one; there is no one like Him. It is this belief in his uniqueness that prevents people from creating graven images or pictorial paintings of Him. There are symbols or emblems but no images for nothing can be compared to Him. Perhaps, this is the reason foreign observers of the people’s religion mistakenly assume that Olodumare is a withdrawn God about whom men are uncertain.

- He is Omnipotent. As omnipotent, the Yoruba believe that with Olodumare, nothing is impossible. They describe Him as “Oba a se kan” meaning the King whose works are done to perfection. The idea is that when He sanctions something it is easily done. The Yoruba have a saying: “A dun ise bi ohun ti Olodumare lowo si, a soro bi ohun ko lowo si (anything that receives the approval of Olodumare is easy; what he does not sanction is difficult)”. This is why He is known as “Olorun Alagbara”-the powerful God. He is also called “oba ti dandan re ki iseke”, the king whose biddings are never unfulfilled.

- He is Immortal. The Olodumare never dies. The Yoruba believe that it is unimaginable for Elemi (the owner of life) to die. They praise him by singing “A ki igbo iku Olodumare” meaning He is an unmovable rock that never dies.

- He is Omniscient. Olodumare knows everything. There is nothing hidden from Him. He is the wise one. Everything is within the reach of Olodumare. The knowledge of God penetrates all things (Mbiti, 1975). The Yoruba people often describe Him as “A-rinu-rode Olumo okan ” (the one who sees both inside and outside).

- He is King and Judge. The Yoruba see the Olodumare in the important position of King. The people often call Him “Oba Orun” (the King of Heaven). He is sometimes referred as “Oba dake dajo”, the King who sits in silence and dispenses judgment.

- Olorun, the sky God. Olorun, who is known as Olodumare, is the Sky God which is reminiscent to the Judeo-Christian God and the Muslim Allah. The sky God is the creator of all things and other deities, and, like the Nyame of Ashanti and other West African cultures, He stands above and beyond other lesser gods. Unlike other deities, Olodumare is not worshipped, prayers are addressed to him but no sacrifices are offered. Not only does Olodumare create, sustain and protect men, He also shields men from mechanizations of other men. Nevertheless, Olodumare is neither so remote nor unconnected that He does not intervene in affairs on earth. Most of the sacrifices prescribed by Babalawo-the, his priest, are taken to Olorun by Eshu. According to the Yoruba, all men are children of God. As the deity who assigns and controls the individual destinies of mankind, Olorun can be considered as the God of Destiny. What should be emphasized is that the Yoruba give the Supreme Being various names and that the deities do not live independent from the Supreme Being -Olorun. He is their creator.

The Role of the Divinities

To complete the reader’s understanding of Yoruba belief, it is also important to understand the divinities. The paper will now identify the divinities and explain their roles.

- Eshu, the Divine Messenger. Eshu, also known as Elegba or Elegbara, is the youngest and cleverest of the deities. He is the divine messenger who delivers sacrifices prescribed by the Babalawo to Olorun after they have been placed at his shrine. The shrine is made up of a simple chunk of literate (red sand) found in Ife, Nigeria. The Yoruba people believe Eshu is a trickster who delights in making trouble; that he serves other deities by making trouble for human beings who offend or neglect them. As an illustration, let’s say Sango, a God of Thunder, desires to kill a person with lightning. He must first ask Eshu to clear the road for him. Eshu may use various punishments at his disposal. The Yoruba knows Eshu as the law enforcer because he punishes those who fail to make sacrifices prescribed by the high priests and rewards those who do. When any of the deities desire to reward those on earth, they send Eshu to do it. Western scholars have made concerted efforts to paint Eshu as the equivalent of the Judeo-Christian “Devil”. This is not true. Eshu’s role is that of a messenger who delivers sacrifices to Olorun and does good for other deities. His remarkable even-handedness in his role as divine enforcer is not consistent with identification as Satan by Christians and Muslims (Bascom 1969). Regardless of what deity one serves, everyone prays to Eshu frequently so that he will not trouble them.

- Ifa, the God of Divination. Ifa is the god (deity) of divination and a close friend to Eshu. He is known as the clerk for other deities and he is thought of as the high priest (known in the Yoruba language as Babalawo). Babalawo is often described as a learned man or scholar because of his knowledge and wisdom in the Ifa verses. He serves as the interpreter between the gods and humans. Olorun, the Supreme God, gave him power to speak for the gods and communicate with human beings through divination. For example, when a god of Thunder or any deity wants a special sacrifice, he sends messages to the human beings on earth through Ifa. Importantly, Ifa is the one who transmits and interprets the wishes of Olorun to mankind. He prescribes the sacrifices that Eshu carries with him. Whatever personal deities one may worship, all believers in the Yoruba religion turn to Ifa in time of trouble. Based on the advice of the Babalawo, appropriate sacrifices to Eshu are identified and made through Eshu to Olorun. Not all worshippers of Ifa can become Babalawo. The title of Babalawo is only given to special worshippers who have a vast mastery of Ifa. It requires an expensive initiation plus years of apprenticeship to learn the figures, sacrifices and medicines.

- Odua, the Creator of the Earth and His Allies. Odua, is known as Oduduwa. The people of Yoruba believe that he is the creator of the Earth. He is considered as the progenitor of all Yoruba and the first to rule the earth as king of Ife.

- Orishala, the God of Whiteness and His Allies. Orishala or Oshala is best described as the God of Whiteness. He is believed to be the creator of mankind, having made the first man and woman. He has the role of fashioning the form of human beings in the womb before they are born. Working in the darkness with a knife, he shapes their bodies like a carver, and then separates the arms, legs, fingers and toes and opens the eyes, nose and mouth. He is also called Olorun the sculptor. Those that he fashioned as albinos (afin), hunchbacks (abuke), cripples (aro), dwarfs (arara) and mutes (Odi) are sacred to Orishala. They are not the result of mistakes; he makes them to mark them as his worshippers so that his worship will not be forgotten. Orishala is known as “King of the White Cloth” (Obatala). His worshippers may wear other clothes, but white is the proper attire.

- Ogun, the God of Iron. Ogun is the God of Iron and the patron of all those who use iron tools. He is known to be the patron of hunters, and various warriors and, thus, God of war, a patron of blacksmiths, barbers and, in recent times, a patron of locomotives and automobile drivers. The Yoruba’s believe that without Ogun, people could not have their hair cut, farms could not be tilled, paths and water holes would be overgrown with weeds and no one could have made fire without the strike lights which were used before matches were imported. The other deities are dependent on Ogun because he clears the path for them with his machete. He is renowned as a blacksmith and a warrior. If Ogun is annoyed or fighting with a person any of the following could cause the death of that person. For example, the person may be bitten by a snake, shot by a hunter, injured in a traffic accident, cut with a knife or a blacksmith may pound his finger. Ogun is always used for swearing an oath just as Christians use the Bible for swearing oaths.

- Oranmiyan, the Son of Ogun and Odua. Oramiyan or Oranyan is said to have two fathers, Ogun and Odua. A myth tells how Ogun brought back many slaves from war and gave them all to Odua, the king, except a woman known as Lankange. Because Ogun loved Lankange, he kept her himself. When Odua learned of Ogun’s deed, he commanded Ogun to bring Lankange to him. Before Ogun did, he explained that he had intercourse with the Lankange. Nevertheless, Odua took Lankange as his wife. When Lankange gave birth to Oranmiyan, the son was half white skinned like Odua and half black skinned like Ogun (Bascom, 1969).

- Shango, the God of Thunder. Shango is the God of Thunder and the son of Oranmiyan. Living in the sky, he hurls thunderstorms to earth killing those who offend him or setting their houses ablaze. Shango fights with troublemakers and those who use bad medicines to harm others, as well as worshippers who offend him. Shango is likened to fire because when he spoke, fire came from his mouth. He is revered for his magical powers. According to myth, Shango left Ile Ife (a town in Southwest Nigeria) when he was defeated in a magical contest and hung himself. When lightning flashes, his worshippers shout: “The King does not hang himself” (Oba ko so).

The people of Yoruba, like the Akan of Ghana, have acknowledged Olorun ‘s providential care and other lesser gods that people approach when in trouble. It is believed that most of the lesser gods are agents of Olorun or the Supreme God. Olorun does not destroy life, he creates and nourishes life. He is the one who assigns destiny. When Olorun gives you sickness, he provides one with the appropriate medicines. Before a child is born, the guardian souls appears before Olorun, the Sky God to receive a new body, new breath and its destiny for its life on earth. Kneeling before Olorun, this soul is given the opportunity to choose its own destiny. It is believed that the soul may make any request be it reasonable or unreasonable. Destiny involves a fixed day upon which the soul must return to heaven and it involves the individual’s personality, occupation, and luck. The time of one’s death cannot be postponed, but other aspects of one’s destiny may be modified by human acts. The deities help individuals enjoy the destiny promised by God (Olorun). As a result, throughout one’s life, one makes sacrifices to his ancestral guardian and the deities. The charms and medicines are prescribed by Babalawo to assist individuals when in trouble. When one is in trouble, one consults a diviner of the God of Ifa (Babalawo) to determine what should be done to improve one’s lot on earth.

The Yoruba believes that when one dies, one makes farewell visits to the clan members. If a person lived a full span of life, his multiple souls proceed to the afterworld where the Sky God lives. When the soul reaches heaven, the soul gives an account before Olorun. If a man has been good and kind on earth his souls are sent to good heaven (orun rere). If his deeds have been bad, such as poisoning his neighbor, committing murder and engaging in deceit he is condemned to bad heaven (orun buru) or to “orun apadi” (hell) by the Sky God. Those who did not live their full life remain on earth as ghosts. For example, one whose life was cut short by an automobile accident will exist on earth as a ghost. One thing is certain about the destiny assigned; any mortal cannot change it.

If every human being comes to the world with a prefixed destiny, and if Olorun is so kind, how do the Yoruba’s explain occurrences of premature death? The people in Yorubaland try to react to such incidents in the following ways:

- First, the person might have offended the lesser gods thereby bringing the punishment to himself.

- Second, the person might have been destined to the occurrence and this is what he requested from Olorun before being born.

- Third, a Yoruba person may blame other persons for putting a “spell” on him thereby causing the misfortune.

Consequently, the Yoruba people believe in Olorun’s power of benevolence yet they hold that it is possible for both men and supernatural powers to induce men to engage in certain acts that will interfere with Olorun’s appointed destiny for each individual human being. So when misfortunes occur no one blames Olorun instead the Yoruba believe that it is the untrustworthiness of agents (deities) of Olorun that are responsible.

God in Yoruba Belief presents evidence that the concept of the Supreme Being is a Monotheistic principle of the Yoruba religion. According to Idowu, Yoruba religion is a “diffused monotheism” in that the many Yoruba divinities are “no more than conceptualizations of attributes of Olodumare” the Yoruba Supreme God. Like a Yoruba ruler, or oba, Olodumare reigns supreme in the distant sky and rules the world through his intermediaries, the orisha. The sky dwelling Olodumare is transcendent, all knowing, and all-powerful. Unlike the orisha, he has no temples or priests, and no sacrifices or offerings made to him because his will cannot be influenced or changed. Yet Olodumare may be invoked by anyone, anywhere, at any time and let him know their needs. He is seen as invisible. Because of the invisibility of God, the Yoruba make no concerted efforts to erect a shrine of Him or any kind of “physical representation”

@Wizzy, Afro Bodhisattva, Entrepreneur, Physical Anthropologist, Freelance researcher of African Studies, culture, tradition and heritage, CEO Dolomite Aggregates LTD and Founder MBA Métissage Boss Academy & @metissagesanguemisto.

References

- Agyakwa, K. O. (1996). The problem of evil according to Akan and Whiteheadian metaphysical systems. ÌmódòyE: A journal of African philosophy, 2, 45-61.

- Awolalu, J. O. (1979). Yoruba beliefs and sacrificial rites. London: Longman Group Ltd.

- Bascom, W. (1969). The Yoruba of southwestern Nigeria. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- Idowu, E. B. (1962). Olodumare: God in Yoruba belief. Ikeje: Longman Nigerian Plc.

- Idowu, E. B. (1975). African tradition religion. Maryknoll, N. Y.: Orbis Books.

- Lucas, J.O. (1948). The religion of the Yorubas. Lagos, Nigeria.

- Mbiti, J. S. (1975). Introduction to African religion. Postsmouth: Heinemann Educational Books, Ltd.

- Niemark, P. J. (1993). The way of Orisha. New York: Harper Collins.

- Opoku, K. A. (1978). West African traditional religion. Accra, Ghana: FEP International Private Ltd.

- Parrinder, G. (1954). African traditional religion. Westport: Greenwood Press.

- Parrinder, G. (1967). African mythology. New York: Peter Bedrick Books.

- Parrinder, G. (1969). Religion in Africa. New York: Praeger Publishers.

- Ray, B.C. (2000). African religions: Symbol, ritual and continuity (2nd ed). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

- Tidjani-Serpos, N. (1996). The postcolonial condition: The archeology of African knowledge: from the feat of Ogun and Sango to the postcolonial creativity of Obatala. Research in African Literatures, 27, 3-19.